The history of the toller

The settlers arriving to North America from France and England brought the hunting traditions from Europe to the new continent. They knew about the red dogs, and they knew that ducks could be hunted with red dogs.

In America, they came in contact with the natives, the indians. In many indian tribes, the dogs played an important part, especially when they were hunting. One of these tribes were the Mi´kmaqs, living along the Atlantic coast from Maine up to Newfoundland and the peninsula that would get the name Nova Scotia.

Before the settlers

In Howard Russel´s book “Indian New England before the Mayflower”, we learn more about the natives and their dogs. ”Our view of the Indian household would be incomplete unless it included dogs – perhaps a half-dozen to the family, in proportion to the master´s standing. They were likely to be slim, with foxlike heads and the look of a wolf … Indian dogs were extremely sagacious, so a traveler in the Niagara country said. They would obey a low-voiced command – even a sign from the master´s hand – and could be trained to lie quiet in the bow of a canoe, then leap into the water to retrieve a duck or goose that the master had brought down.”

There is also a description of a special duck hunting technique: “Morning and evening were the times for ducks and geese. Following well-known flyways, these birds settled at night in river meadows and salt marshes, or rested at ease on the smooth water. The hunters would drift in quietly in canoes, light torches to cause sudden confusion among the birds, and knock them down with clubs or paddles. Then a specially trained canoe dog, sitting in the bow, would jump into the water and retrieve the game.”

Acadia

The French colony Acadia was founded 1604 and the French settlers early made good contact with the native tribes. They had peaceful relations and mixed marriages were common. So, naturally they shared what they knew about ducks and red dogs, and using dogs to retrieve the fallen ducks.

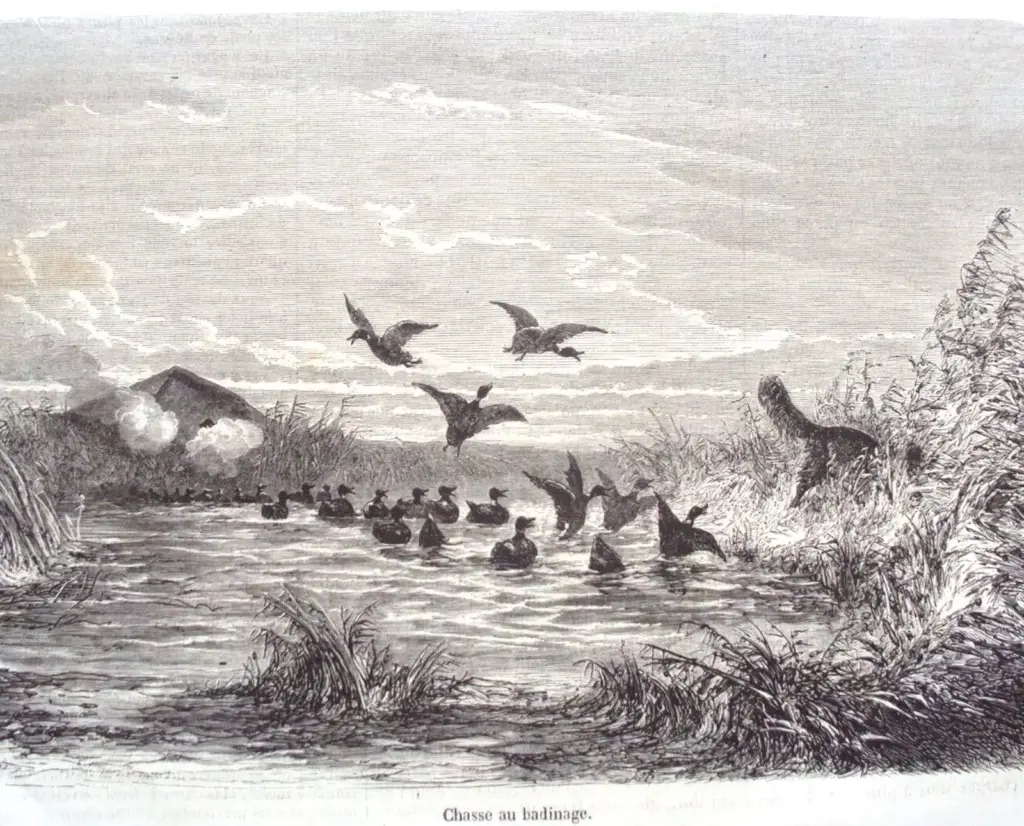

The first description of “tolling” might be in a book from 1672 by Nicholas Denys, a French explorer & colonizer, “The description and natural history of the coasts of North America (Acadia)”.

In it, he mentions that foxes were known to lure waterfowl close enough to shore to catch them and that “We train our dogs to do the same, and they also make the game come up. One places himself in ambush at some spot where the game cannot see him; when it is within good shot, it is fired upon, and four, five, and six of them, and sometimes more are killed.” After that, the same dog trained to lure the ducks was also expected to retrieve them.

Denys’ book have been seen by several other authors as proof that the tolling hunt was invented in Acadia …

… However, who is the “we” Denys refers to? And what were “our dogs”? Was Denys really referring to the hunters in New France (Acadia) and their native dogs, or was he simply referring to the hunters and dogs back home in France?

When the British took Acadia in 1713 and renamed it Nova Scotia, all the ingredients were in place in this region for the development of a specialized breed of tolling dog. Spaniels and retrieving dogs were common along the seaboard; the French and English knew they could lure ducks and the Mi´kmaqs and other tribes used them for retrieving on water; there was an abundance of game; and plenty of coast lines, shorelines and lakes.

What´s in the mix?

It is unknown for sure what “breeds” or types of dogs went into the mixing bowl to create the Toller.

The “breeds” described in the books from the 18th and 19th century were not breeds like today.

There was no pedigree, no record of a dog´s lineage, and it is safe to say that if a dog looked like and behaved and worked like a “spaniel” it was considered a spaniel. There was probably some spaniels, the French Brittany (Breton), and of course the native dogs used by the Mi´kmaq people. Later on, there are photos and notes of farm collies, Irish setters, cocker spaniels, St. John´s dogs (a Canadian breed no longer existing) and Chesapeake Bay retrievers mixed with the red dogs. The Cheasapeake Bay retriever is a likely candidate (the toller pups and Cheasey pups are supposed to look remarkably similar), and Cheasapeake Bay retrievers were also used all along the eastern seaboard when hunting ducks.

One surprisingly popular theory can be dismissed as a legend.

There were no foxes involved in the origin of the tollers, and there were no cross-breeding between dogs and foxes. Dog-fox hybrides (or “doxes”) has not been scientifically verified and they should be genetically impossible, since the two animals diverged over 7 million years ago and they have a different numbers of chromosomes. Even if a dox would have existed (and there is a supposed dox on display at Grosvenor Museum in Chester, UK), it would never be fertile.

By 1900 or so the basic type and appearance of the Little River Duck Dog in Nova Scotia had been established.

All along the Atlantic coast

Although Nova Scotia was the undisputed capital of duck tolling, the practice was not exclusively Canadian. American sporting journals of the mid-1800s contains detailed references to “toling” (the second “L” would be added sometime after the Civil War).

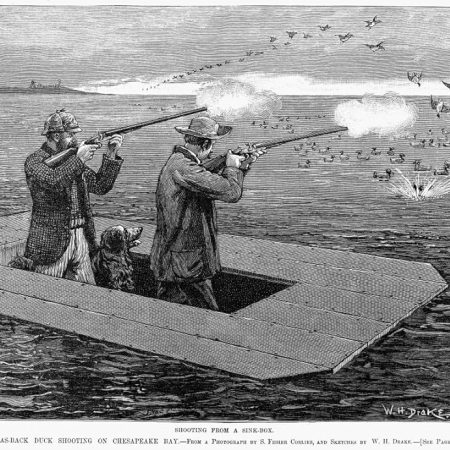

America’s tolling mecca was Chesapeake Bay, with some 19th-century breed historians maintaining that tolling was actually invented there. Whether this is true or merely the boast of patriotic Americans, it is certain that by the turn of the 20th century, tolling was a way of life for hunters up and down the Atlantic coast, as far south as the Carolinas.

“Well, said B., I suppose now you’d like to see some duck-tolling? I’d like to be told, I replied, what tolling is.

He declined to answer my question and said the only way to find out was to see it for myself. We made for a sheltered cove and were shortly crawling on our hands and knees through the calamus and dry, yellow-tufted marsh grass, which made a good cover almost to the water’s edge. Joe left the dogs with us and, going back into the woods, presently returned with his hat full of chips from the stump of a tree that had been felled. …

Then Joe commenced tolling the ducks. He threw a chip into the water and let his dog go. The spaniel skipped eagerly in with unbounded manifestations of delight. I thought it for a moment a great piece of carelessness on Joe’s part. But in went another chip just at the shallow edge, and the spaniel entered into the fun with the greatest zest imaginable. Joe kept on throwing his chips, first to the right and then to the left, and the more he threw, the more gayly the dog played. For twenty minutes, I watched this mysterious and seemingly purposeless performance, but presently looking toward the ducks, I noticed that a few coots had left the main body and had headed toward the dog. Even at that distance, I could see that they were attracted by his actions. They were soon followed by other coots and after a minute or two, a few large ducks came out from the bed and joined them. Others followed these, and then there were successive defections of rapidly increasing numbers.

The more wildly he played, the more erratic grew the actions of the ducks. They deployed from right to left, retreated and advanced, whirled in companies, and crossed and recrossed one another. Stragglers hurried up from the rear, and bunches from the main bed came fluttering and pushing through to the front to see what was up in the water. Then, by the aid of their wings, sustained themselves a moment, and sitting down, swam rapidly around in involved circles, betraying the greatest excitement. And still the dog played, and played, and gamboled in graceful fashion after Joe’s chips.

By this time the ducks were not over two hundred yards away. Taking heart in their numbers, they were approaching rapidly, showing in all their actions the liveliest curiosity. It was an astonishing and most interesting spectacle to see them marshaling about, to see long lines stand up out of the water, to note their fatuous excitement and the fidelity with which the dog kept to his deceitful antics, never breaking the spell by a fatal bark or disturbing what was taking place all about.

By this time the nearest skirmishers were not a hundred yards off. As Joe threw the chips to right or left and the dog wheeled after them, so would the ducks immediately wheel from side to side. On they came until some were about thirty yards away. These held back, while the ungovernable curiosity of those behind made them push forward until the dog had a closely packed audience of over a thousand ducks gathered in front of him.

“Fire!” said B., and the spectacle ended in havoc and slaughter. We gave them the first barrel sitting, and as they rose, the second. We got thirty-nine canvas-backs and red-heads, and some half dozen coots.”

The description above is from an article published in Scribner’s Monthly in November 1887. The author wrote that the dogs “… belonged to the breed known as Chesapeake duck-dogs . … a short-haired water-spaniel, drawn from imported stock, and peculiarly adapted to the cold water, and has been cultivated for years and is greatly prized by the sportsmen of Maryland.” He also wrote that further north in eastern Canada, another kind of dog had been cultivated for years and was greatly prized by the sportsmen of Nova Scotia, in particular by hunters in the area of Little River.

The tolling with Little River Duck Dogs was common in Nova Scotia and tolling with other kinds of red dogs was done all along the Atlantic Coast in the 1800s … but slowly, decade after decade, it became less common. Other forms of hunting came in fashion, other forms of duck hunting was seen as more effective, and fewer and fewer hunted as a way to put food on the table for the family or to sell duck meat at the local market.

Saved from oblivion

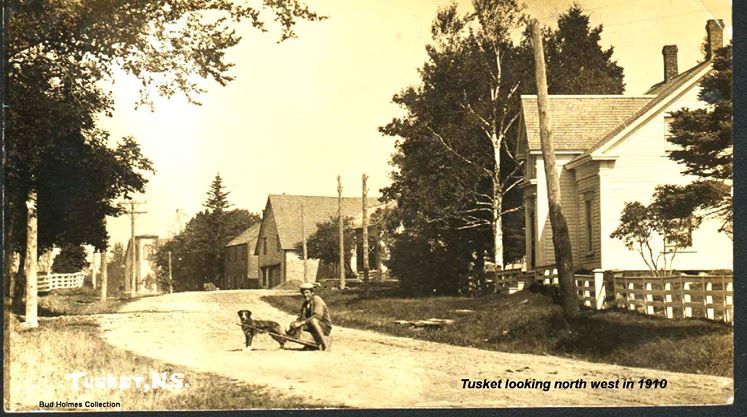

In 1918, in the magazine “Rod and Gun in Canada” the author writes “that the Western part of Nova Scotia is the only place in the World where the Tolling Dog is bred and trained”.

The author´s initials is H.A.P.S.

HAP Smith was a skilled hunter, fisherman, author, dog breeder and relentless promoter of the Tolling dogs, contributing to many journals and magazines from the 1880s to the 1920s. He wrote about tolling and tollers, and in 1915 summed it up: “If you are a dog man, the first time you see a tolling dog your attention will at once be arrested.”

During these years, two distemper epidemics around 1910, had almost wiped out the entire population.

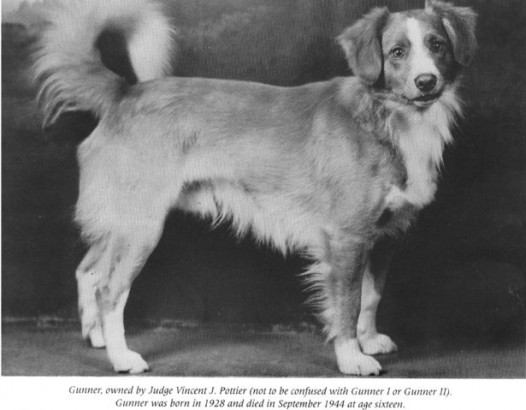

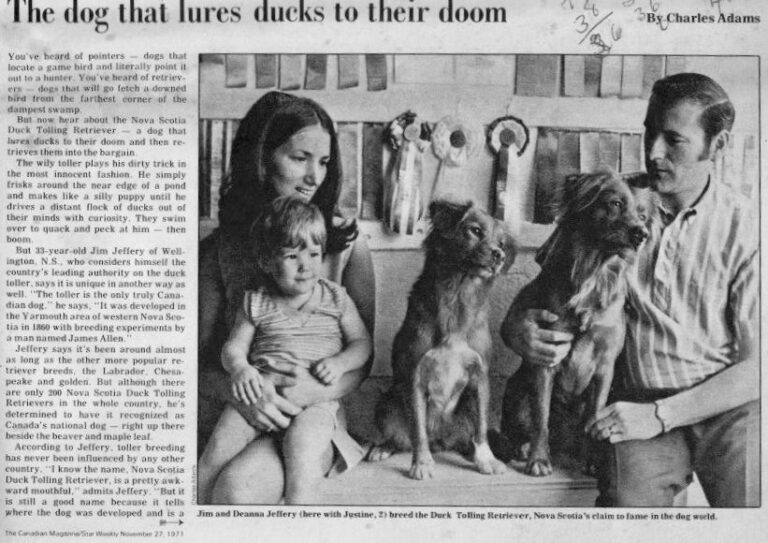

When Colonel Cyril Colwell in the early 1920s became fascinated with the tollers, he visited Smith several times and he also set out to save the breed. He travelled to all parts of Nova Scotia to find breeding stock, and owned more than 80 tollers over a thirty-year period.

The tollers were still rare and almost unknown outside of Nova Scotia. When one of the most famous athletes of his time, the baseball icon Babe Ruth, in 1936 visited Yarmouth to fish and hunt, he was so thrilled by the tollers that he brought one back to the United States.

In 1936, the Canadian Kennel Club (CKC) opened up for discussions, and Colwell in the 1940s could prove that his tollers to be three generations purebred. The first breed standard was written and approved in 1945. The World had a new unique dog breed.

The name of the breed was also new – the term “retriever” had been included in the name. In all the years since the 1800s, the little red dogs had been called Little River Duck Dogs or Yarmouth Tollers …

15 tollers, most of them owned by Colwell, were registered by the CKC in 1945, and then no more dogs were registrered until 1960. The regulations set up to register proved too hard, and many toller owners didn´t have the pedigree records needed or bothered with the long procedure. The next tollers registered came from Hettie Bidewell´s Chin-Peek kennel. Slowly in the 60s more and more tollers were entered in the stud book and CKC registers.

In these early years one breeder, avid hunter, and toller enthusiast stands out and plays a major important role in keeping the toller as a hunting dog breed – Avery Nickerson at Harbourlights kennel. Many of our European tollers will have one or more Harbourlights tollers in their ancestry.

The Canadian breed club was established in 1974. The American Toller Club was formed ten years later, and in 1982 the first tollers were exported to Europe, to Denmark. The same year FCI (Federation Cynologique Internationale) recognized the toller breed, enabling them to be shown in all FCU countries.

In 1984 tollers were arriving to Sweden from Canada and from Denmark. Tollers quickly became popular and the Swedish Toller Club was formed just two years later and arranged its first toller speciality in 1988. The Swedish toller population is by far the largest in Europe, the breed club is the largest, and the Swedish toller speciality each August finds 400-500 tollers from most of Northern and Central Europe entering.

The tollers were permitted to enter the official retriever field trials within the Swedish Spaniel and Retriever club already from the 80s.

The next step was taken in the late 90s when a group of toller enthusiasts and hunters started work on the natural step … field trials based on the unique way of hunting that our breed was born to do – the tolling tests.

Next chapter: Tolling tests